Ancestors, Animism, and the Meeting of Faiths

Aluk To Dolo

The Way of the Ancestors

The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram

My fascination with animism began many years ago when I was living in Nepal. During that time, I stumbled across a book in a dusty corner of a Kathmandu bookstore, The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram. Little did I know then that this book would open my mind to a way of thinking about the world that I had come across before but never really taken a deeper dive into. Abram’s exploration of how humans perceive the natural world as an interconnected, living entity deeply resonated with me. The idea that the world is full of spirit, with each stone, tree, and animal carrying its own consciousness, seemed to mirror the teachings of many indigenous cultures, including the Torajans.

As soon as I arrived in Toraja, I could feel the presence of death everywhere. Banners lined the streets for upcoming funerals, and coffin huts stood along the roadside, waiting to carry the dead to their final resting places. In the highlands of Toraja, the boundary between the living and the dead is not a fixed line. It moves fluidly, shaped by the rhythms of nature and the enduring presence of ancestors. Here, animism is a living force that weaves through daily life, binding people to their land and their lineage. In Torajan culture, death is an ongoing relationship maintained through ritual and an abiding respect for the unseen world.

When I arrived in Toraja, I was eager to speak to someone who strictly adhered to the Aluk To Dolo tradition. This ancient animistic belief system, rooted in the worship of natural spirits and ancestral guidance, is gradually fading in the face of modern influences, particularly Christianity. The Torajan culture, rooted in its animist belief system known as Aluk To Dolo (“The Way of the Ancestors”), has undergone significant transformations over time, particularly with the influence of external religions and colonial powers. It’s a wild blend of unique faiths and traditions, where animistic practices like Aluk To Dolo intertwine with Christianity and Islam, creating rituals that honour ancestors while incorporating prayers and blessings from newer religions.

During my time in Toraja, I had the privilege of meeting a Toporenge, a revered ritual leader responsible for maintaining the sacred practices of Aluk To Dolo. His home was perched on the mountainside, and after presenting an offering of tobacco and beetle nuts, I was welcomed into his home, a structure 300 years old, never renovated, and steeped in history and tradition. The floors creaked beneath our feet, held together by the spirits of ancestors, and the air was thick with the presence of the past.

Inside the house, I met the Toh Makula—four family members who had died but still rested in a state between life and the afterlife, awaiting their final rituals. Among them was the Toporenge’s grandfather, a Toh Makula who had been in the house for 20 years. The Toporenge’s father and uncle were also resting in their coffins. His mother, who died just two months prior, was laid on the wooden floor in a cool, dark room, where the air could circulate through the floorboards, aiding in the natural drying process during the wet phase of her transition. The family spoke with deep reverence about the importance of adhering to traditional rituals, which they believe maintain harmony between the living and the dead. In their worldview, death is a deep, spiritual connection to the cosmos and ancestry, carried forward through ritual and tradition.

I sat sipping on coffee with the Toporenge, his wife, and their two sons, who had been declared as infants to follow the Aluk To Dolo religion, untouched by the wave of Christianity that now dominates much of Toraja. They spoke about the traditions and the importance of strict adherence to certain rituals in ceremonies essential to maintaining harmony between the living and the departed.

Despite the dominant presence of Christianity and Islam in the region, with around 86% of Torajans identifying as Christian and 8% practising Islam, elements of Aluk To Dolo remain deeply ingrained in their culture, particularly in death rituals. This intersection of faiths is not unusual in Toraja. I witnessed firsthand how many Christians still incorporate animistic practices into their ceremonies, especially those surrounding death and the afterlife. I was invited to a funeral where prayers and blessings from both Christian and animistic traditions were woven seamlessly together in the same ceremony. The Christian priest would offer a prayer, followed by a ritual where the family made offerings of food and sacrifices to the ancestors. It was a striking example of how spirituality can be fluid, adapting to new beliefs without erasing the old.

For the Torajans, Aluk To Dolo is a way of life that shapes their relationship to nature, death, and the cosmos. It influences everything—from how they build their homes to how they engage in rituals surrounding life’s transitions. The respect for the natural world is integral to this belief system. It’s a belief that the spirits of the dead walk among the living, guiding and protecting them, and that all things in nature—mountains, rivers, trees—are alive with spirit. To me, this is a powerful reminder that spirituality is interwoven with both life and death, from the smallest pebble to the grandest mountain or the vast expanse of a rice field, reaching across to both the living and the dead.

A local Toporenge, standing alongside his wife and two sons, with their 300-year-old home in the background.

The buffalo horns on a Torajan Tongkonan signify the family’s social status and wealth, with each horn marking a successful funeral. More horns indicate higher prestige.

The Fusion of Animism, Christianity, and Islam in Torajan Beliefs

My time in Toraja also allowed me to witness the fascinating intersection of Christianity, Islam, and animism—three spiritual forces that are not merely coexisting but are interacting and integrating in ways that are both meaningful and natural. Christianity, introduced to the region by Western missionaries in the 20th century, played a significant role in reshaping the religious life of the Toraja people. However, this shift did not erase their ancient animistic traditions. Instead, I observed how Aluk To Dolo adapted, merging with Christian and Islamic principles in ways that felt organic rather than forced. Spirituality in Toraja is deeply connected to identity and history.

In Toraja, the rituals surrounding death are seen as a continuation of life, a bridge between the physical and spiritual realms. During my time there, I attended a funeral where the grieving family, who identified as Christian, nonetheless performed an animistic ritual involving the sacrifice of water buffalo—a symbol of the deceased's soul's journey to the afterlife. After the ritual, the priest offered a prayer in line with Christian beliefs, asking for the deceased’s soul to rest in peace. This blending of animism, Christianity, and Islam is a holistic approach to life and death. The rituals are enriched by the contributions of all three spiritual practices, and each offers something essential: animism’s connection to the land and ancestors, Christianity’s teachings on salvation, and Islam’s respect for the deceased.

The presence of animism in Toraja, particularly around death, continues to influence how Torajans view their relationship with both the living and the dead. The Aluk To Dolo system remains foundational, especially in death-related rituals, which are a collective affair. I attended a ceremony where extended family members participated in a highly ritualised funeral that included communal offerings and symbolic sacrifices. These acts weren’t just for the deceased; they were seen as a reaffirmation of the living’s commitment to their ancestors and each other.

I also witnessed the struggle that arises from the tension between modern religious influences and traditional practices. The slaughter of dozens or even hundreds of buffalo during funerals is central to Torajan culture, but this practice often clashes with the teachings of Christianity and Islam, which can view such ceremonies as excessive. As I spoke with several community members, it became clear that maintaining ancestral customs—especially those around death—while navigating the expectations of Christianity and Islam, was an ongoing balancing act. It was hard not to feel the weight of this intricate dance between honouring the past and adapting to the present.

The integration of these three belief systems reflects a resilient and adaptive culture. Christianity and Islam have undoubtedly brought new elements to Toraja culture, but they have not erased the ancient animistic practices that are central to the community’s identity. Instead, these beliefs continue to coexist, inform one another, and enrich the rituals and ceremonies that bind the people of Toraja to their ancestors, their land, and the unseen forces that guide them.

In Toraja, the living and the dead are inextricably linked. The spirits of the ancestors are never far away, always present in the rituals, the land, and the very air the Torajans breathe. It is a culture where the ancestors walk with the living in the wind that rustles through the rice fields, in the creak of the traditional tongkonan homes, and in the quiet moments when the boundary between this world and the next feels impossibly thin.

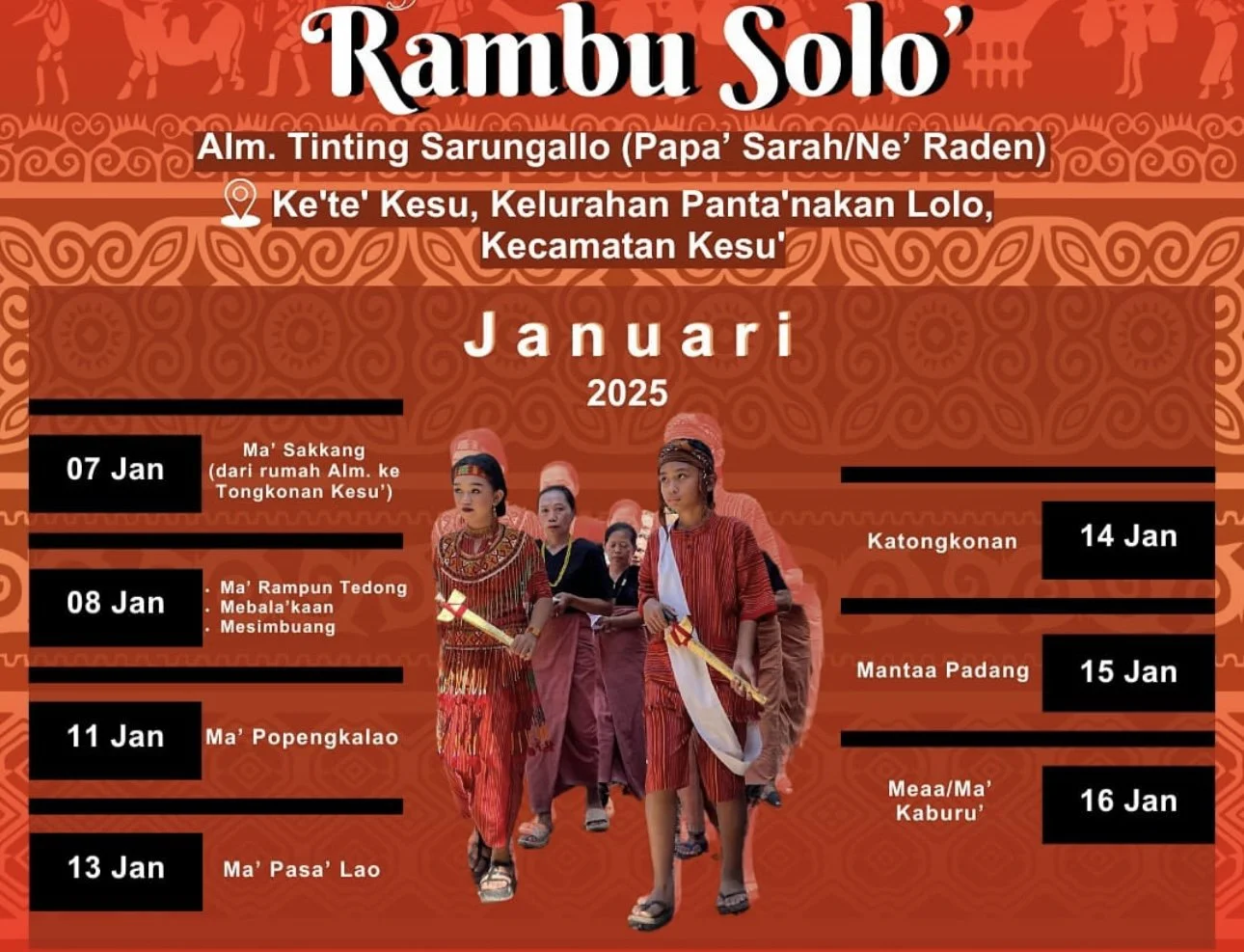

A Poster for a Multi-Day Rambu Solo’

(Grand, High-Caste Funeral)

Villagers transport the deceased on an Airong—a wooden and bamboo platform that supports the Erong (coffin).